|

Monday, May 15, 2006

Monday, May 15, 2006

If Numbers Don't Add Up, Try Connecting the Dots

By MICHELLE YORK

BRIGHTON, N.Y., May 12 - Last Christmas, David Kalvitis watched as his wife and elder son unwrapped a gift from a relative with good intentions.

Inside were a couple of puzzle books: games of numbers and grids that have become an international sensation. "Sudoku?" he said, raising his arms in exasperation.

Max Schulte for The New York Times

Max Schulte for The New York Times

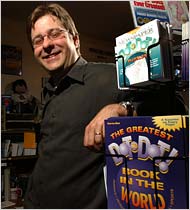

David Kalvitis scaled back his graphic arts business in 2000 so he could create dot-to-dot puzzles in his home in Brighton, N.Y.

Few people appreciate how difficult, even lonely, it is to be the anti-sudoku guy.

For six years, Mr. Kalvitis has created and published his own brand of puzzle books, an unusual collection of dot-to-dot games. His compilations are sold at bookstores and syndicated weekly in eight newspapers. Loyal fans from around the country and in Europe have written him letters.

One man's message to the world: Dot puzzles aren't just child's play.

Almost every year, he wins an award from a parenting group or a toy association, including a 2006 best book award from the Oppenheim Toy Portfolio, a consumer guide to children's books and games.

His business, which he operates out of his suburban colonial style home here, has been slowly but steadily growing, enough to support his wife and two sons. But it is the flip side of the phenomenon of sudoku.

In sudoku, the puzzler must fill in the blank squares of a grid so that each nine-cell row, each nine-cell column and each nine-cell mini-grid contains all the numbers from one to nine. Experts believe it made its debut in America in 1979, though some say its origins can be traced to around 2800 B.C. in a Chinese game called magic squares.

In the last two years, the popularity of the game has skyrocketed. Book sales have topped 5.7 million copies, according to a recent Publisher's Weekly survey. For example, a shopper at a Barnes & Noble near Mr. Kalvitis's home in this Rochester suburb can find five shelves of sudoku books, from "Sudoku for Dummies" to "Mensa Sudoku."

"I do one about once a week," said Veit Elser, a Cornell physics professor, about sudoku. "I find them satisfying."

Mr. Kalvitis has been watching the sudoku success with mixed emotions: he is happy that people are doing puzzles, but very aware that the game competes for bookshelf and newspaper space against his dot puzzles. "That came on, like, huge," he said. "It's really annoying, too."

Unlike sudoku, which seems to be everywhere, including magazines, the Internet and newspapers, the dot puzzles have spread under a marketing plan that may seem haphazard. For example, Mr. Kalvitis is syndicated in newspapers in Slovakia, but not in nearby Rochester.

Still, a picture is emerging. "From what I hear, readers enjoy the puzzles," Lukas Fila, a projects manager for the two Slovakian papers where the dot-to-dots are published, wrote in an e-mail message.

For 13 years, Mr. Kalvitis, 43, worked as a graphic artist, mostly creating advertisements that he believed were soon bound for the recycling bin. Puzzles were always in the back of his mind. As a child, he had created crosswords made of inside jokes for his sister. As a newlywed, he made dot-to-dot cards for his wife. When she connected the lines in a valentine, she saw a rose.

For seven years, while he worked as a graphic artist, he tried creating untraditional dot-to-dots Ń ones that could not be easily discerned and involved more than a simple outline. He has continued to produce complex puzzles, some of which can be used to teach basic geometry. These dot-to-dots cannot be completed with one continuous line, end-to-end.

In 2000, he came out with his first book, scaled back his graphics arts business and began devoting himself to his puzzles full time. He called a series of books "The Greatest Dot-to-Dot Book in the World."

Then he began calling stores and setting up exhibits at toy fairs. When a local Barnes & Noble kept placing his books only in the children's section, he grabbed an armful and put them in the puzzles section. Later, he said, he returned and saw they had sold out. "I'm going to get in trouble for that," he said. "But it was in the name of science."

Today, he has eight books in print, all self-published. The printing runs have grown from 3,000 to 12,000 copies. He said he never makes it through a year without having to reprint all of his books. Barbara E. Lee, 55, from San Francisco, found them in a gift catalog. "Sometimes I lay on my stomach and do one," she said.

She has considered sudoku books too. "Which I find boring," she said. "Who cares if whatever adds up to whatever."

Reprinted with permission from The New York Times

|

|